Review — The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and Its Solutions

Review:

The Divide by Jason Hickel, not to be confused with The Divide by Matt Taibbi or even The Great Divide by Joseph Stiglitz, is about global inequality, its current status, its historical origins, and its potential solutions. If 50 minutes is too long I’ve found reading only the quotes makes for a decent shortened version.

Hickel is an anthropologist at the London School of Economics. Having grown up in rural Swaziland he has had a closer and more extended look at the realities of global poverty than most.

Despite the rosy depictions of the world we see in the Op-eds and pop science books of Jeffrey Epstein’s rolodex, Jason Hickel remains skeptical. In his view, statistics spouted by organizations which ostensibly exist to reduce global poverty seem more committed to the impression of reducing poverty than the process itself. Throughout university I was subjected to the Hans Rosling narrative that we are too pessimistic about global poverty. (The mantle is now carried by Steven Pinker.) I think there is a genuine upside to that narrative to an extent. Depressed apathy towards the well being of billions of people is not the path to ending poverty. That being said, neither is self satisfied indifference.

Hickel acknowledges success where applicable, but quite clearly thinks the status quo merits much more criticism than praise. Going in I anticipated Hickel to be very passionate even hyperbolic in his claims. My impression from his online reputation was that his heart was in the right place, but he’s far too ideologically committed to be realistic about the state of the world. After reading the book this critique feels like projection.

Forming a compelling narrative about the state of global inequality is impossible to do without being interdisciplinary to an extent. The downside is as your narrative draws from more subjects there is more room for knowledge gaps. I’m sure there’s room for valid criticism, but you won’t find much from me. No author I’ve read has effectively synthesized political economy, history, social change, and even a bit of systems thinking quite as well.

Summary:

Having grown up in rural Swaziland Hickel returned working with World Vision to reduce poverty. While international charity helps in the margins he felt it was nowhere near the level needed to meaningfully change the country’s status.

Interventions implemented to help the people were missing the point. Countries don’t need palliative charity. They need systemic change.

Examples:

Countries couldn’t afford patent protected drugs to keep their own citizens healthy and frequently aren’t allowed to use generic drugs without a lengthy and expensive international legal battle.

Farmers in the global south couldn’t make a living since western countries were sending subsidized food.

The government couldn’t do its job because they were in debt and forced by western countries to abandon the needs of their people to prioritize repayment.

Bottom Line: The problems of Swaziland were not solvable within Swaziland’s borders.

Bringing this information to a World Vision manager led to warnings of being too political. If beneficial changes were actually implemented (Pharma patents, International Trade rules, Debt Resolution) they would lead to funding cuts, especially since the stakeholders which benefit from these issues also happen to fund World Vision. We need to somehow find non political solutions to political problems.

The Global Development Industry

“When Myths fall apart, revolutions happen.”

The myth of successful development is waning among the public, but it remains among the development field which has failed to deliver on its promise to end world hunger, or global poverty.

“ Within a decade no child shall go to bed hungry” — Henry Kissinger, 1974 at the World Food Summit

Poverty Reductions which have been made are largely inadequate for human survival let alone dignity. The genuine successes achieved have been in Child & Maternal mortality which have plummeted in recent decades.

In 1960 the end of colonialism Per capita income in the richest country was 32x that of the poorest. The development industry predicted the gap would narrow. It quadrupled to around 134x1.

The Good News Narrative

It may seem to be a harmless bedtime story for white liberals, but the good news narrative serves an important political tool.

“The good-news narrative enjoins us to believe that the global economic system is on the right track. It implies that if we want to eradicate suffering, we should stick with the status quo… for anyone who has an interest in maintaining the present order of distribution- the global one percent, for instance — the good-news narrative is a useful story indeed.”

The good news narrative works largely due to moving goalposts. I didn’t bother noting all the organizations and their individual goalposts, but the point he seems to make is that they work backwards from their conclusion of general success and find favorable time ranges & price levels to suit the narrative. Whether this is due to ideological blindness or corruption is not discussed.

Shortly after the Millennium Declaration was adopted, the UN rendered it into the Millennium Goals that we know so well today. During this process, the poverty goal (MDG-1) was diluted yet again — this time behind closed doors, without any media commentary at all. First, they changed it from halving the proportion of impoverished people in the whole to halving the proportion in developing countries only. Because the population of the developing world is growing at a faster rate than the world as a whole. This shift in the allowed the poverty accountants to take advantage an even faster growing denominator. On top of this there was a second significant change: they moved the starting point of analysis from 2000 back to 1990. This gave them much time to accomplish the goal, extended the period of denominator growth and allowed them to retroactively claim gains in poverty reduction that were long before the campaign actually began. This backdating took particular advantage of gains made by China during the when hundreds of millions were lifted out of extreme poverty, and deceptively chalked them up as a victory for the the Millennium Development Goals.

One criticism I’ve seen leveled at Hickel is that he insists on using absolute numbers of people in poverty as opposed to proportions so he can make it look like it’s getting worse when in fact the increase is a function of population growth. Now I discover he’s just using the metrics which have already been used as the goalpost for global poverty. When he applies their own metrics without their revision he finds underwhelming results.

Jason Hickel upon being called a pessimist has replied that there’s nothing optimistic about resignation to the status quo. I think in a way he points out an intrinsic appeal of the good news narrative. If a system seems unchangeable, then it is mentally unpleasant to demand change. Why put yourself through the stress?

Global Poverty

Measuring all the world with the same poverty line is troublesome to say the least. Even so raising the nominal IPL (International Poverty Line) over decades has been subtly lowering it in real terms.

“So the new $1.08 poverty line was actually lower in real terms than the old $1.02 line. And lowering the poverty line made it appear as though fewer people were poor than before. When the new line was introduced, the poverty headcount fell literally overnight, even though nothing had actually changed in the real world. This new poverty line was introduced in the very same year that the Millennium Campaign went live, and it became the campaign’s official instrument for measuring absolute poverty. With this tiny alteration, a mere flick of an economist’s wrist, the world suddenly appeared to be getting better.”

Similar patterns recur in multiple global poverty organizations as the years go by.

Global estimates of poverty within a country can also vary wildly from a country’s reported estimates. Sri Lanka in 1990 reported a poverty rate of 40%. The World Bank using the IPL reported 4%. In 2010, the Mexican government reported a 46% poverty rate. The World Bank reported 5%.

The Asian Development Bank concedes $1.25 is too low to be meaningful. Raising it by 25 cents would lead to a 1 billion increase of people in poverty.

Hickel argues $5 is a more suitable line. The mean average of all national poverty lines in the developing world comes out to around that.

However if a line of $5 per day were used, the global poverty headcount would be 4x what the World Bank would have us believe. (4.3 billion) It would also show a billion people have been added to the global poor since 1981.

Poverty has been genuinely declining in China and East Asia, the two places which coincidentally were not forced into structural adjustment programs.

“Everywhere else poverty has been stagnant or getting worse in aggregate, and this remains evident despite the World Bank’s attempts to doctor the figures.”

Global Hunger

The global standard for hunger also leaves something to be desired.

The standard for hunger goes by the minimal caloric standards for a sedentary lifestyle. The problem is the global poor generally have very demanding manual jobs requiring up to 3000 or 4000 calories per day.

Hickel also points out hunger doesn’t count to the UN unless it lasts for over a year, which means if families can’t afford adequate nutrition year round, they are still considered to be adequately fed by global standards.

“The FAO presupposes without invoking any supporting evidence that 11 months of hunger is not detrimental to human health… the idea here seems to be to simply keep people alive just to satisfy the metrics while caring little about the kinds of lives they are able to live.”

And once again we have enough food to feed everyone on earth 3000 calories a day. Hunger is a problem of distribution. (The global distribution of food is inseparable from the global distribution of resources which is inseparable from the global distribution of power.)

Even given a higher line of calories, nutrient shortages should still be taken into account which adds yet another standard that is ignored by clumsy generalized metrics.

Even if things were getting somewhat better in the aggregate, it wouldn’t justify inaction.

“The morally relevant comparison of existing poverty is not with historical benchmarks but with present possibilities. How much of this poverty is really unavoidable today? By this standard, our generation is doing worse than any in human history.”

Intervention

Walt Whitman Rostow: An economist and Foreign policy adviser to Eisenhower argued underdevelopment was not political, but technical. Not to do with Western intervention, but to do with internal issues. Key to development is of course accepting Western aid and advice. Kennedy hired him into the State Department and LBJ promoted him to National Security adviser.

His book, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, was used as a PR device to depoliticize inequality. It was targeted at the global South. This ideological campaign against developmentalism was unsuccessful. The developing nations indifference to the ideas espoused had real negative effects on western powers ability to extract labor and resources from these countries.

“In response they intervened covertly to overthrow dozens of democratically elected leaders across the south, replacing them with dictators friendly to Western economic interests who were then propped up with aid… Rostow knew full well what was going on. Indeed he may have been involved in the US backed coup against the leader of Brazil in the 1960s, which took place during his tenure in the state department.”

Later we discovered such violent and unseemly methods were avoidable. In the 1980s we discovered our ability to use our power as creditors to dictate economic policy across the global South. “Effectively governing them by remote control.”

Structural Adjustment Programs reversed all the economic reforms won by the global South. “They went so far as to ban the very policies that they had used for their own development, effectively kicking away the ladder to success.”

These programs were sold as precondition for development in the global south. Naturally it did the opposite.

“Economies shrank, incomes collapsed, millions of people were dispossessed, and poverty rates shot through the roof. Global South countries lost an average of $480 billion per year in potential GDP during the structural adjustment period. It is now widely acknowledged by scholars that structural adjustment was one of the greatest single causes of poverty in the global south, after colonialism. But it proved to be enormously beneficial to the economies of the North.”

“Poverty doesn’t just exist. It is created.”

Aid

Despite the financial movement of global aid to the global South, it is dwarfed by the financial movement of resources going the opposite direction. Aid is good, but it does not make up for the damage wrought by the aid givers.

Trade Misinvoicing: False prices on trade invoices to move money out of poor nations to tax havens depriving developing countries of about $875 billion / year.

Abusive Transfer pricing: Multinationals shift profits illegally between subsidiaries in different countries. Evade taxes, launder money, or circumvent capital controls.

“For every dollar of aid that developing countries receive they lose $24 in net outflows.” (Ratios vary by country of course.)

Some of this damage is “caused by the very groups that run the aid agenda.” The World Bank profits from global South debt. The Gates Foundation profits from the intellectual property regime keeps life saving medicine and important technology well out of the reach of countries that need it.

“It is delusional to believe that aid is a commensurate, let alone honest and meaningful solution to this kind of problem. The aid paradigm allows rich countries and individuals to pretend to fix with one hand what they destroy with the other, dispensing small bandages at the same time as they inflict deep injuries, and claiming the moral high ground for doing so.”

Growth & Poverty vs Inequality

Our singular fixation on growth ignores problems of distribution. Current economic growth is not spread according to need. It is spread according to power. (Which is the kind of the opposite of need)

The poorest 60% of humanity receive only 5% of all new income generated by global growth.”

Eradicating poverty without changing this distribution will optimistically take centuries.

Given the present distribution of income, global per capita income would have to be around 1.3 million dollars per year for the poorest among us to make $5 per day. Climate Change would wipe out human life on earth before this happens. Inequality is an actual problem. If our system can’t address it, changes are required.

He elaborates on this somewhat absurd yet provocative thought experiment in a piece for the Guardian.

Part 2 Concerning Violence:

Our conceptions of poor countries as independent from rich countries is ahistorical and counterproductive.

The development narrative of the west tends to ignore the exploitative properties of the Core nations of Europe. “The Divide” began well before the industrial revolution.

“Economists often speculate that the global South failed to develop because of a lack of capital. But there was no such lack. The wealth that might have provided the capital for development (precious metals in Latin America and surplus labour in Africa) was effectively stolen by Europe and harnessed to the service of Europe’s own development. The global South could theoretically have developed as Europe did were it not for the plunder of its resources and labor… It is impossible to examine the economic growth of the West without looking at the base on which it drew.”

Peasants before industrial capitalism had what they needed most for a stable livelihood which was access to land which can be used for : “Farming crops, grazing livestock, hunting game, drawing water, excavating peat, and cutting wood for heating, cooking, and shelter.” They were not rich, but they had the basic right to habitation.

In the 15th century, wealthy nobles to profit from the wool trade turned the land into sheep pasture by abolishing the right of habitation. They privatized common land, and fenced it off from the public. The process was called Enclosure. It was obviously not a peaceful process.

After a long struggle the displaced peasants had no choice but to sell their labor, which is why London grew much faster and much earlier than other European cities. A majority of people lived in slums and factory work was miserable. 16 hour days for low pay was the norm. Cheap labor destroyed the existing guild system.

I tried to illustrate Hickel’s narrative below. These basic principles of forcing people off their land and into low wage factory jobs will recur throughout the book. The elements will change from enclosure to NAFTA & from Dickensian London factories, to Congolese Mines etc. What’s important isn’t the elements themselves, but how they influence each other each time.

Demand for Wool increases so demand for land to graze sheep increases. This leads to the practice of enclosure. Enclosure abolishes the right to habitation making subsistence lifestyle is less and less viable. When subsistence living goes down, urbanization goes up. People participate in wage labor, increasing the labor supply, decreasing wages, therefore decreasing production costs and increasing profit margins. For bonus I’ll link my luddite piece from a while back.

“They became the world’s first mass consumer population, for they depended on markets for even the most basic goods necessary for survival.”

“Even in England, people didn’t welcome this new system with open arms. On the contrary. they protested and rebelled against it, for it violated long-standing cultural expectations about people’s basic rights to habitation, to the means of subsistence, to the means of life. The goal of the enclosure movement was not just to displace people from their land, but — much more profoundly — to eradicate these cultural expectations. Why is this history of England useful to our understanding of global poverty? Because the process of enclosure not only marks the origin of mass poverty as a historical phenomenon, it also illustrates the basic logic of the process that would produce poverty across the rest of the world.”

Bonus: The contemporary relevance of of how property is originally distributed is discussed a bit here by Hernan De Soto. He compares British Enclosure and and California’s

Imperialism

A key justification for imperialism is improvement of the land selon John Locke. I’ll share an excerpt from Howard Zinn.

“He said that he was really sorry about what had happened to Indians, but that there was a good reason for it. The continent had to be developed and he felt that Indians had stood in the way, and thus had had to be removed. ‘After all,’ he remarked, ‘what did you do with the land when you had it?’ I didn’t understand him until later when I discovered that the Cuyahoga River running through Cleveland is inflammable. So many combustible pollutants are dumped into the river that the inhabitants have to take special precautions during the summer to avoid setting it on fire. After reviewing the argument of my non-Indian friend I decided that he was probably correct. Whites had made better use of the land. How many Indians could have thought of creating an inflammable river?”

Imperialism in India

India’s famine in the late 1800s was avoidable in any truly rational economic system. Grains could have been shipped from areas of surplus to areas of shortage. Instead it was sent to guarded areas before being shipped to Europe.

“In 1877 and 1878 during the worst years of the first drought they shipped a record 6.4 million tons of Indian wheat to Europe rather than relieve starvation in India… The Indian famines of the late 19th century were not a natural disaster as the British insisted at the time. They were the predictable consequence of imposing a foreign market logic that saw fit to eliminate basic food security and sacrifice tens of millions of people in the service of profit. The famines had nothing to do with endogenous economic problems; rather they were caused by India’s incorporation into the emerging capitalist world system.”

No part of this was a choice by the Indian people.

Imperialism in China

When China tried to maintain autonomy over their economy the British started selling Opium on their black market. After China clamped down on the trade, the British invaded. In the end, Europeans sold their manufactured goods on Chinese markets even as they protected their own markets against Chinese competition. The Chinese share of the world economy went from 35% to 7%.

While British apologists may claim these events ultimately were a gift historical data shows the opposite.

“In the middle of the 18th century, the average standard of living in Europe was a little bit lower than in Asia. Even as late as 1800, per capita income in China was ahead of Western Europe, and per capita income for Asia as a whole was better than that of Europe as a whole.”

Literacy rates were higher in China than in Europe including among women. Birth rates were lower. In India worker incomes were higher in the 18th century. Indian Artisans had a better diet than the average European.

“During the colonial period in India there was no increase in per capita income from the time the East India Company took power in 1757 to the time of national independence in 1947. In fact during the last half of the 19th century — the heyday of British intervention — income in India declined by more than 50%. And it was not just incomes that collapsed. From 1872 to 1921, the average life expectancy of Indians fell by 20%. In other words the subcontinent was effectively de-developed.

While India and China watched their share of global GDP diminish, Europeans increased their own share from 20 to 60 per cent during the colonial period. “Europe didn’t develop the colonies. The colonies developed Europe.”

Imperialism in the Congo

King Leopold’s regime led to 10 million deaths, about half the population via either direct Belgian aggression or the destruction of local economies and dispossession, starvation, and spread of disease.

Failing to reach rubber quotas would mean losing hands a technique similar to Columbus’s previous methods of imperialism. This savagery helped subsidize lush city of Brussels, home of the EU.

There was not enough labor to go around at first. Again people were reluctant to abandon their subsistence lifestyle. Backbreaking labor in plantations and mines for obscenely low wages was a tough sell. The solution of course is to remove the subsistence alternative.

They were pushed off their land and into unproductive areas, in addition to new taxes being levied in order to force more and more people into the wage labor market. Over time the labor market would grow bigger and bigger preventing even the potential for competition and higher wages. Unions of course were out of the question.

Racism was (is)a powerful tool to justify the treatment of non white people around the world.

A New Deal in the West

During the Depression economic theories of the time were exposed. Hoover cut government spending to spur investment, while others speculated wages needed to be slashed. It didn’t help. New economic theories were supplied.

“conventional views began to crumble and new economic theories emerged from the rubble. The problem, people began to realise, had to do with the internal contradictions of capitalism itself. Capitalists seek to maximise their profits by increasing productivity and decreasing the costs of production. The easiest way to decrease the costs of production, of course, is to push down workers’ wages. But if this process is left unchecked, eventually wages get so low that workers cannot afford to buy the products they produce. Demand goes down, and the market becomes glutted with excess goods with no one to buy them. Goods quickly lose their value, businesses stop producing and the economy slows down. This is what happens when capitalism is left to its own devices: it generates such extreme inequality that the whole system simply seizes up.”

“It was the British economist John Maynard Keynes — mustachioed member of London’s famous Bohemian scene — who brought this critique to prominence. In light of his findings, he proposed a very different way of dealing with the Depression. He argued that governments should not cut spending and wages, but instead do exactly the opposite: increase government spending, open up the money supply and encourage higher wages. These measures, he said, would get people buying again, stimulate aggregate demand and therefore boost the economy back to life: what we might call ‘demand side’ economics.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt came to power in the United States in 1933, he began to do precisely that. His New Deal — a vast programme Of government-funded projects, such as New York’s Lincoln Tunnel and Montana’s Fort peck Dam — put armies of unemployed Americans to work with good wages. Massive government spending had what Keynes called a ‘multiplier effect’: by transforming government money into workers’ wages, workers gain consumer power that creates new opportunities for private businesses that spring up where the cash is plentiful, like trees around an oasis. When the Second World War gained pace it proved the point: government spending on factory production for the war effort had the same effect, boosting employment (the US reached full employment during the war), increasing wages and stimulating demand. Economic growth soared and — with higher wages for the poor and higher taxes on the rich — inequality was dramatically reduced.”

I kept this as simple as I can since it’s not the main point of this essay, but I think it’s a good way to show how an economy can get into a rut, and how Keynes proposed to get it going again.

So starting at the bottom. The Depression leads to a decrease in investment spending which leads to a decrease in private sector success which leads to a decrease in employment which leads to a decrease in wages which leads to a decrease in consumption which leads to a decrease in private sector success, again and so on in a reinforcing feedback loop. This continues until we add the top half.

Government spending, and later wartime spending led to state funded projects which increased employment, wages, consumption, private sector success and back to employment reversing the feedback loop. This government spending led to increased wages for the poor but required taxes on the rich particularly during the war. This tragedy may explain why such stimulus has gone out of fashion. (At least we kept the spending on war.)

“As part of the New Deal, the United States also implemented a universal Security programme, provided affordable housing and, with the GI Bill, handed out large university tuition subsidies for veterans. In Britain, a growing union movement — propelled largely by coal miners — brought to power Clement Atlee’s Labour Party, which rolled out the National Health Service, free education, public housing, rent controls and a comprehensive social security system, as well as nationalising the mines and the railways. Many politicians on the right were willing to go along with it, hoping that granting the working class a fairer deal would stave off the social discontent they feared might spark a Soviet-style revolution. They also hoped it might prevent the rise of fascism, which had attracted Germans beleaguered by their severe economic crisis. By ensuring stability and welfare across the industrialised world, Keynesian principles were designed to prevent another world war.”

Post War Global South

“For the first time, global South countries were free to determine their own economic policies. And seeing how well Keynesian economics was working in Europe and the United States, they were quick to adopt its basic principles: state-led development, plenty of social spending and decent wages for workers. And they added one crucial piece to the Keynesian consensus: a desire to build their economies for their own national good, rather than solely for the benefit of external powers. This was the era of ‘developmentalism’. Latin America’s Southern Cone — Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and parts of Brazil — became an early success story.”

New wealth was more equitably shared than before. Life expectancy increased faster than ever recorded from the end of colonialism to the 1980s. Inequality was reduced both within and between countries.

G77: African and Asian states met in Indonesia to share ideas form economic ties and resist colonialism from the US and Soviet Union. They sought a genuine third way.

“The developmentalist revolution, and the South’s growing political power was eroding the foundations of the world system that Europe and the United States had come to rely on.”

Eisenhower after hiring the Dulles brothers who had previously represented JP Morgan and United Fruit Company painted developmentalism as Communism in the making. US foreign policy did not distinguish between Soviet Communism and Developmentalism as they both threatened the interests of western capitalists.

Hickel details US actions against Mossadegh in Iran, Arbenz in Guatemala, & Goulart in Brazil.

One of my favorite tidbits unfortunately left out by Hickel is why Guatemalan Land Reform so infuriated United Fruit Company.

When I cheat you it’s just business. When you cheat me, it’s personal.

Hickel goes on to list more examples of US intervention. Like a lot more. The main idea is that the departure from developmentalism was whack, nonconsensual, and did not lead to growth in any meaningful way.

Neoliberalism Comes Home

“Chile was the first victory in the Chicago-led counter-revolution. But it remained impossible to impose Neoliberal policies in the United States and Europe — the Keynesian system was far too popular and, unlike in Chile and other Latin American countries, where democracy had been suspended, voters would quickly reject any attempt to roll it back. Yet this consensus began to change in the 1970s. Keynesianism had delivered high growth rates through the 1950s and 1960s, but by the early 1970s the US and Europe were beginning to face a crisis of ‘stagflation’ — a combination of high inflation and economic stagnation. Inflation rates soared from about 3 per cent in 1965 to about 12 per cent ten years later. According to standard Keynesian theory, when inflation rises, unemployment should decrease. But this time something strange was happening: unemployment was rising along with inflation. This dealt a serious blow to the credibility of Keynesian ideas, and created a golden opportunity for critics to offer up the alternatives they had been formulating — and testing — behind the scenes.

What set off the crisis of stagflation? Most scholars point to a few key events that happened during the Nixon administration. For one, Nixon was engaged in expansionary monetary policy — in other words, he was effectively printing money. On top of this, government spending on the Vietnam War at the time was spiraling out of control. As international markets worried that the US would not be able to make good on its debts, the dollar began to plummet in value and contributed further to inflation. And while all of this trouble was unfolding, another crisis hit. In 1973, OPEC decided to drive up the price of oil. The price of consumer goods suddenly shot up too, because the energy required to produce and transport them was more expensive. And because production became more expensive, economic growth slowed down and unemployment began to rise. It was a perfect storm.”

Starting from the top: Expansionary monetary policy increases money supply, which decreases the value of the dollar.

Orange: The Vietnam war requires government borrowing which reduces confidence and therefore value in the dollar.

Green: Higher oil prices means higher production costs, which meant higher consumer goods cost. The same amount of money could buy less. Lower value.

Blue: As production costs get higher, economic growth slows and employment decreases. We get unemployment and inflation at the same time.

“The crisis of stagflation was the direct consequence of specific historical events. But the neoliberals rejected these explanations. Instead, they insisted that stagflation was a product of Keynesianism — the consequence of onerous taxes on the wealthy, too much economic regulation, labour unions that had become too powerful and wages that were too high. Government intervention, they claimed, had made markets inefficient, distorted prices and made it impossible for economic actors to act rationally. The whole market system was out of whack, and stagflation was the inevitable consequence. Keynesianism had failed, they claimed, and the system needed to be scrapped. In the end, this argument prevailed. Not because it was correct, but because it had more firepower behind it — and when it came to swaying public opinion it helped that Hayek and Friedman had both won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for their ideas along these lines, in 1974 and 1976 respectively. The argument held a great deal of appeal for the wealthy, who were looking for a way to restore their class power, and they were more than happy to step in to support it. The crisis of the 1970s became a perfect excuse to dismantle the social contract of the post-war decades.”

His statement that the argument prevailed because of the firepower behind it is correct, but whether or not Keynesianism can be completely absolved of inflation is more open to discussion. For more on how the social contract was undemocratically dismantled I’ll link my Volcker Shock piece.

Hayek & Friedman were the saviors for the capitalist class. Formed Mont Pelerin society and took over the Chicago school of Economics.

“For Friedman and his followers, their great enemy was not only Keynesianism in the United States, but also social democrats in Europe and the developmentalists in the global South. They saw all of these systems as contaminated forms of capitalism that needed to be purified. There was price- fixing to make basic goods more affordable. There were minimum wage laws to protect workers from exploitation. Certain services — like education and healthcare — were kept out of the market altogether to ensure universal access. These policies were improving people’s lives, but Friedman claimed that they were doing hidden harm by disrupting the equilibrium of the market. Price controls, subsidies and minimum wage laws should all be abandoned, and the state should sell off any services that corporations could run at a profit, including education, healthcare, pensions and national parks. Governments should cut back social spending so as not to interfere with the labour market. Taxes should be at a flat rate. And corporations should be free to sell their products anywhere in the world. If implemented, he claimed, these policies would lead to unprecedented growth and prosperity.”

The school was obviously flooded with corporate donations, (Dark Money summary here.) Still it did no good convincing most Americans who were content with Keynesianism. The global South was of course content with developmentalism as well, but it didn’t matter.

Debt

The G77 was splintered by the weaponization of Aid. Henry Kissinger helped shift the most important UN decisions from the General Assembly to the Security Council controlled by the richest nations. Then Foreign Aid was used to divide the poorest countries of the world from the G77.

When OPEC raised oil prices they saw an influx in more cash than they knew how to invest. Hundreds of billions of petrodollars flooded US banks at the same time western economies were floundering. The money was largely loaned to countries of the global South who sought to build up their economies. Dictatorships were the most eager to accept as they could immediately siphon it off into their bank accounts or businesses. (David Graeber covers this sequence of events in his book, Debt: the First 5000 Years.)

This practice has not disappeared. Recently a World Bank Economist resigned after higher ups blocked research showing a correlation between foreign aid and increased deposits in financial havens.

Debt levels reached as high as half a country’s GDP, which isn’t inherently problematic, but the money was largely used to cover rising oil prices rather than investing in productive capacity. The West’s ongoing recession took a toll on their raw material export revenues as well. Interest rates of course were sent sky high by Paul Volcker to combat inflation, and since these loans were variable interest rate, the loans interest rates went sky high as well.

Mexico was the first to default. Brazil and Argentina followed.

Since the banks were in the midst of a free market revolution they demanded salvation from the US government which stepped in to force countries to pay back their loans. The tool was the IMF which would force poor countries to stop government spending and use their money to repay loans to western banks. “The IMF came to act as a global debt enforcer.”

Reposting my Volcker Shock systems map. Notice the yellow on top. Interest rates increased real debt costs as the decline in consumption led to reduced export revenues. Third world debt became impossible to pay, and their economic autonomy was taken from them as Hickel explains.

“This is how the plan was supposed to work: the IMF would help developing countries finance their debt on the condition that they would agree to a series of ‘structural adjustment programmes’ . Structural adjustment programmes, or SAPS, included two basic mechanisms for debt repayment. First, developing countries had to redirect all their existing cash flows and assets towards debt service. They had to cut spending on public services like healthcare and education and on subsidies for things like farming, food and infant industries; they also had to privatise public assets by selling off state companies like telecoms and railways. In other words, they had to reverse their developmentalist reforms. The savings gleaned from spending cuts and the proceeds of privatisation would then be funnelled back to Wall Street to repay debts. In other words, public assets and social spending retroactively became collateral in the repayment of foreign loans — an arrangement that was, of course, never agreed at the time the loans were signed. Global South countries were made to pay for the banks’ risky practices with billions — even of dollars taken from ordinary people. This trillions — amounted to an enormous transfer of wealth from the public coffers of impoverished global South countries to the richest banks in the West.

The second mechanism was slightly less direct. Countries that were subject to structural adjustment programmes were forced to radically deregulate their economies. They had to cut trade tariffs, open their markets to foreign competitors, abolish capital controls, abandon price controls and curb regulations on labour and the environment in order to ‘attract foreign direct investment’ and make their economies more ‘efficient’. The claim was that these free-market reforms would increase the rate of economic growth and therefore enable quicker debt repayment. As the bankers put it, countries would be able to ‘grow their way out of debt’. Debtor countries were also forced to orient their economies towards exports, to get more hard currency to repay their loans. This meant abandoning the import-substitution programmes they had used to such good effect during the developmentalist era. In addition, structural adjustment programmes required debtors to keep inflation low — a kind of monetary austerity — because the bankers feared they would use inflation to depreciate the value of their debt. This was a big blow to global South countries, not only because it prevented them from inflating away their debt, but also because it barred them from using monetary expansion to spur growth and create employment.

So SAPS introduced a three-part cocktail: austerity, privatisation and liberalisation. These principles were applied across the board, not just in Mexico, Argentina, Brazil and India — the first victims of structural adjustment — but in every country that was placed under the control of the IMF, regardless of their local economic conditions or the particular needs of their people. It was a one-size-fits all blueprint, handed down from above by Washington-based technocrats — the central planners of an emerging global economic order that claimed, ironically, to detest central planning.

The promise was that these policies would alleviate the debt crisis and prevent it from recurring. But this was a very subtle sleight of hand — a kind of ruse. The structural adjustment reforms themselves had nothing to do with the real causes of the crisis. The real causes of the crisis were exogenous: they had to do with exorbitant interest rates and declining terms of trade, over which global South countries had no control. But the IMF had no intention of tackling these problems, for to do so would require challenging the interests of Western governments and their commercial banks. Instead, the IMF acted as though the problem was endogenous, as though it had to do with problems in the local economy. So the IMF pushed domestic economic reforms as if they were a response to the crisis when in fact they were not. The crisis was simply an excuse for rolling out an economic agenda that Washington had long been seeking to impose.”

The SAP’s were able to enforce Chile’s economic policies around the world without “the embarrassing inconvenience of dictators and torture chambers.” Liberalisation which was supposed to improve growth did the opposite.

“Developing countries lost roughly $480 billion per year in potential GDP during the 1980s and 1990s as a result of structural adjustment… losses due to structural adjustment outstripped gains from aid by a factor of five.” — Robert Pollin

The IMF is supposed to reduce instability. The World Bank is supposed to reduce poverty. Either they are more ideologically committed to free global markets than actual results, or their stated goals are a facade.

Capitalism hits limits when it comes to finding new sources of profit.

Market Saturation: Consumers have what they need, business slows down.

Ecological Depletion: Cost of resources goes up as supply dwindles.

Class Conflict: Pushing/keeping down wages leads to social instability.

Erik Olin Wright has a more thorough list of issues I summarize here.

With limited options to invest, capital leads to over accumulation. Savings interest rates are generally lower than inflation. Capital begins to lose value, which is unacceptable.

Solutions:

Long term projects like education, R&D, & infrastructure to increase productivity. These solutions are empirically successful, but they require long term thinking and wealth redistribution, which is unpalatable to the people who have the power to actually make these decisions.

Other solutions are to drive down oil prices (cheaper production), Increase the workforce, (lower wages) or Create new markets, (Privatization & Debt investment, Student Loans/Credit Cards)

A solution in the midst of the 1970s stagnation was to open up foreign countries to new consumer, labor and investment markets. This is the purpose of the World Bank and IMF. High interest guaranteed returns.

Development projects funded by the World Bank required poor nations to hire American contractors, and buy American materials from American businesses at higher costs. Every loan ostensibly given to develop poor countries increases demand for private American enterprise. “American Businesses get up to 82 cents in new purchases for each dollar that the US government contributes to the bank.”

Structural Adjustment opening new labor markets combined with improved transportation led to a global race to the bottom for the cheapest labor with the lowest standards. Labor was effectively disciplined around the world.

“It would be impossible to overestimate how important the World Bank and IMF are to the countries of the G7. Not only did they become the most powerful tool in the fight against developmentalism. They also offered a spatial fix to the crisis of western capitalism, which was bumping up against its own limits in the late 1970s. By turning poor countries into new frontiers for investment, extraction, and accumulation, they allow western capitalism to surmount its limits and carry on without having to confront its own internal contradictions — at least for the time being.”

It’s not about poverty. It never has been. It’s stated goal is to promote private investment and international trade.

Compound Interest

It’s hard to overstate just how insurmountable this debt can be.

“Between 1973 and 1993 global South debt grew from one hundred billion dollars to 1.5 trillion dollars. Of the 1.5 trillion dollars only 400 billion dollars was actually borrowed money. The rest was piled up simply as a result of compound interest. So despite the monumental effort that developing countries make to repay their loans, they are only chipping away at an ever-growing mountain of compound interest and not even beginning to touch the principle that lies beneath which threatens to persist forever.”

Structural adjustment programs which were supposed to reduce debt have failed by its own standards. Debt as a function gross national income has gone up each decade not down.

The countries were afraid to default because they had seen the lengths the US will go to protect their economic interests. (Iran, Guatemala, Congo, Chile etc.)

In Burkina Faso Thomas Sankara was made an example of by France.

“‘The origins of debt lie in colonialism. Our creditors are those who had colonized us before. They managed us then and they manage us now. But we did not ask for this debt,’ he continued. ‘And therefore we will not repay it. Debt is neocolonialism. It is a cleverly managed reconquest of Africa. Each one of us becomes a financial slave. We are told to repay.We are told it is a moral issue. But it is not.’ And then he delivered the clincher: The debt cannot be repaid. If we don’t repay, the lenders will not die. That is for sure. But if we do repay, we will die. That is also for sure.’”

He was assassinated three months later as is tradition.

A solution could be that all countries refuse to pay at the same time, but leaders in many countries benefit from the present arrangement even if their people do not.

Keep in mind:

- Many loans were taken out by dictators.

- The principle has been paid off again and again.

- The lenders favored economic policies are the ones that failed.

“If history shows anything, it is that there’s no better way to justify relations founded on violence, to make such relations seem moral, than by reframing them in the language of debt — above all, because it immediately makes it seem that it’s the victim who’s doing something wrong.” -David Graeber

In the name of choice and freedom, decision making has been taken from democratically elected bodies to unelected bureaucrats in a foreign nation.

America’s own development is not a product of the free trade they espouse (force) upon Latin America today. Hamilton rejected the free trade theories of Adam Smith et al. recognizing their interest was the success of their own economy, not America’s. Protectionism and state support were key to success.

From 1860–1930 we were the most protective economy in the world. Britain had to force free trade elsewhere. “The global south lost their economic independence, because the Americans had gained it.”

Free trade works in theory, and economists prefer theory to the real world which can be messy and disobedient. It reminded me of a quote from Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

“To put it bluntly, the discipline of economics has yet to get over its childish passion for mathematics and for purely theoretical and often highly ideological speculation, at the expense of historical research and collaboration with the other social sciences.”

In fact Hickel cites the same quote in his review of Capital for the London School of Economics.

Free Trade

Hickel elaborates on the shortcomings of free trade theory in similar ways as Ha Joon Chang who he also seems to be a fan of.

“The Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson model sounds so reasonable, on the face of it. It seems so obviously correct. But it has the insidious effect of naturalising global inequalities.The model assumes that each country has a natural endowment of factors of production. In other words it wants us to believe that rich countries have a natural abundance of capital relative to poor countries, which have a natural abundance of cheap labour, as though this arrangement has always been the case — as if it was written in the stars or handed down by the gods.”

But why is labor so cheap there, and capital so abundant here?

“Rich countries have expensive labor because of a long history of unions and strong labor laws, and have abundant capital because of long standing tariff protections that allowed them to develop their industries. Poor countries on the other hand have cheap labor and no capital, because of a long history of colonization, dispossession, unequal treaties and structural adjustment… It takes an inequitable social relationship and gives it an aura of the natural, of the unquestionable. The Heckscher–Ohlin–Samuelson theory runs straight against the evidence of history.”

“While it may be true that free trade increases efficiency in some abstract, mathematical sense, and perhaps even boosts consumption in the short term, it is not a meaningful strategy for long term economic development. In fact the theory itself never pretends to make this claim. It is merely a fancy bit of rhetoric that gets wheeled out by people who stand to benefit from it. In order for economic development to occur, poor countries need to build their capacity for capital intensive industry. This means intentionally insulating their industries from global competition until they are fully prepared to compete on the open market.” (As is the case with every developed nation.)

Another issue with the HOS is perfect factor mobility assumption that capital and labor from one dying industry can simply move into another which is unrealistic to say the least. “The mobility of liquid capital is too perfect, while that of labor and fixed capital is not perfect enough.”

A level playing field between an established powerful multinational company and a developing nation’s infant industry sans protection is not exactly an equitable competition, even if they were technically playing by the same rules. As it happens even playing by the same rules is too much to ask.

Even the WTO’s standards favor developed nations. Poor countries aren’t allowed to subsidize goods, but rich countries subsidize agricultural goods and undercut poor countries agricultural products on the global market.

“It’s subsidies for the rich, and free trade for the poor. In other words because of the selective application of the WTO’s rules, many poor countries are effectively prevented from developing the one sector that free-trade theory says they should develop. Whether they attempt industrial development or agricultural development, they’re blocked both ways.”

So much of this largely boils down to asymmetries in power. If poor countries step out of line they can be crippled by sanctions imposed by rich countries. Poor countries can sanction rich countries as well, but the effects are negligible.

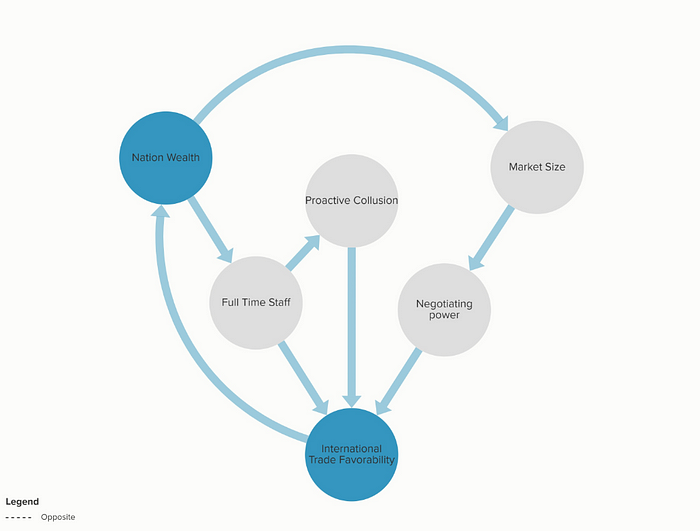

The WTO’s consensus is based on market size which means economic policies are decided largely by whoever already has the most economic power. Rich countries even have special green room meetings to reach an internal agreement before the real process of consensus even starts. When developing nations representatives attempt to enter they are forcibly removed. Richer countries can also afford full time Geneva staff while developing nations have to exercise frugality.

WTO Reinforcing Feedback Loops

Pretty straightforward. High national wealth means a higher market size which means more negotiating power which means more favorable trade which preserves/increases nation wealth in a positive feedback loop. National wealth also allows for a full time negotiating staff, which improves trade favorability and national wealth again, directly and indirectly via proactive green room collusion in a second reinforcing feedback loop.

Meanwhile a low national wealth means a small market size, and no full time staff. Power in the WTO is obviously a zero sum game so the mechanisms which reinforce wealthy countries positions of strength by definition keep poor countries in positions of weakness, perpetuating the existing maldistribution of power.

This situation is widely acknowledged and has led to protests in the global North. The present result is a stalemate. The solution is bilateral trade agreements negotiated between two countries which circumvent the centralized international apparatus.

The first major FTA was the NA FTA. This agreement was not very agreed upon. Voters resisted to the extent that they could in all three countries. Mexican Farmers even protested predicting (correctly) that they could not compete with American subsidized corn. 2 million farmers were obsolesced, their land sucked into consolidated plantations owned by foreign firms. Unemployed farmers were able to seek new opportunities at the sweatshops that the American job creators were now moving South of the border.

Subsidized corn may have decreased food prices, but NAFTA also deregulated food prices so the prices of tortillas almost tripled. Hunger and malnutrition rose accordingly.

“It was a dream scenario for US companies. They get new export markets, new access to land, higher retail revenues, and cheaper labor. Many large Mexican firms benefited too — indeed, that is why the Mexican government agreed to NAFTA in the first place. But ordinary people suffered tremendously… Real wages across the board are lower, and the minimum wage is worth 24% less. 10 years after NAFTA there were 19 million more Mexicans living in poverty than before NAFTA.”

NAFTA also broke the power of organized labor in the US and helped contribute to contemporary US wage stagnation.

NAFTA’s Chapter 11 which is focused on investor state dispute settlement allows investors to sue developing countries for laws that could potentially reduce their expected profits at some point in the future.

Metalclad, a US corporation, sued the state of Mexico for shutting down a hazardous waste landfill that was polluting the water supply that locals depended on. Mexico had to pay $15 million in damages. In Canada, Dow Agrosciences, sued the government for banning the use of its pesticides just because it may cause cancer in humans.

“Corporations are empowered to regulate democratic states, rather than the other way around. This is a frontal assault on the ideas of sovereignty and democracy, and one that is being conducted ironically, once again under the banner of freedom.”

At a certain point all regulations become temporary, expensive, and ultimately ineffective, so countries stop trying. Once again the asymmetry of power rears its head. The state can’t sue investors. The best case scenario is to not have to pay any damages. Arbitration judgements are secretive and undemocratic of course.

“These treaties amount to something like a corporate coup d’état on an international scale. They create an avenue for extraterritorial legislation that bypasses national parliaments a nd any form of democratic discussion, pouring scorn on the idea of elected government. In this sense the ideology of ‘free trade’ overplays its own hand, and exposes itself as farce. The FTAs make it clear that free trade was never meant to be about freedom in the first place.

Indeed, the very things that do promote real human freedoms — such as the rights of workers to organize, equal access to decent public services, and safeguards for a healthy environment — are cast as somehow anti-democratic, or even totalitarian. These freedoms are reframed as ‘red tape’ or as ‘barriers’, even when, as is almost always the case, they have been won by popular grassroots movements exercising democratic franchise. In this sense, democracy itself is targeted, bizarrely, as anti-democratic, inasmuch as it grants voters control over the economic policies that affect their lives.”

The decline in capital controls also means that global investors get to have daily referendums on economic decisions made by developing nations with the ability to withdraw capital investment at will.

“There’s even an iPhone app that jet-setting capitalists can use to redirect their investments on the fly. A new minimum wage law was just passed in Haiti? Better move your sweatshop to Cambodia. Higher taxes on the rich in South Africa? Time to sell your stocks and invest in Ireland instead.”

The World Bank has seemingly innocuous “indicators” in the Doing Business rankings which punish countries that look out for the rights and well being of their own citizens.

“The disturbing thing about these indicators is that they have no sense of balance. They don’t just want lower minimum wages, they encourage countries to abolish minimum wages entirely; they don’t require more modest taxation, they press for zero taxation; they don’t ask for more streamlined trade, they want to cut out all tariffs; they don’t demand fewer regulations on land, they want total freedom of purchase. Countries are rewarded for pushing to these extremes. There is no recognition that some regulations might actually be important to a fair society, or indeed for a stable economy. But the Doing Business indicators are not actually against regulations as such; they are only against regulations that don’t directly promote corporate interests. Regulations that protect creditors and investors — and empower them to grab land and avoid taxes — are considered good.

The Doing Business rankings reduce economic policy to the shallow metrics of private gain. According to this flagship initiative of the World Bank — which is supposedly devoted to creating a world without poverty — nothing matters aside from corporate profit. The well-being of the people, the health of the land, the fairness of the society — none of these count in the brave new world of free trade. Countries are compelled to ignore the interests of their own citizens in the global competition to bolster corporate power. And here’s what may be the most disturbing element of all: the rankings not only inform investors’ decisions, they also determine the flow of development aid, as some aid agencies give preferential support to countries that make progress in the rankings. Forget measures of health, happiness and democracy. Forget gains in wages and employment. In the end, what counts most is the ‘ease of doing business’. If you’re curious enough to look into the methodology behind the Doing Business rankings, you’ll find that it’s not very robust at all. An official review of the report, ordered by World Bank President Jim Kim and completed in June 2013 raised a list of concerns, including that the methodology has not been peer-reviewed.” Indeed, it is based almost entirely on the papers of two of the economists, Simeon Djankov and Andrei Shleifer, both of whom are well-known neoliberal ideologues.”

Due to its ability to dictate political policies in countries across the globe, Hickel refers to this international investor class as the “virtual senate.”

The rise of the virtual senate represents an important innovation in the history of neoliberalism. In the past, neoliberalism was imposed around the world by external powers. But the virtual senate enjoys the power to get countries to impose neoliberalism on themselves, simply by controlling the flow of capital. If a country wants to secure the capital they need for development — or even for survival — they have to kowtow to the wishes of the virtual senate: cut wages, cut taxes, slash regulations.”

“Before the gods of foreign investment, the world is hostage.”

Corruption

Corruption is usually the primary explanation for the poor economic development in the global south. In reality corruption in the form of bribery and theft by government officials amounts to “about 3% of the total illicit flows that leak out of the developing world each year.”

Meanwhile the GFI calculates commercial tax evasion amounts to up to 65% of these illicit flows. “According to GFI, each year up to $1.1 trillion flows illegally out of developing countries and into foreign banks and tax havens.” Outstripping Aid and investment and growing all the while. (6.5% per year)

Two methods of extraction

Hot Money (19% of illicit outflows) Usually used to speculate on interest/exchange rate differences can also provide a means to move money illegally across borders.

Trade Misinvoicing: (80% of illicit outflows) Companies cheat the trade system by misrepresenting the value of an international transaction. The GFI can detect reinvoicing due to the obvious differences in the invoices reported by exporters and importers.

Transfer Mispricing on the other hand is harder to detect. Companies simply falsely report the cost of an item. The majority of global “trade” takes place within not between multinational corporations.

“Transfer mispricing is remarkably easy. All a company has to do is write out an invoice that falsely reports the cost of an item, and then get their trade partner to write out a similarly false invoice on the other side.”

Examples include $4121 toilet paper from China, $2052 Apple juice from Israel, and ballpoint pens from Trinidad for $8500. Each.

“By inflating transfer prices, a company can magically move its money from subsidiaries in high tax countries to subsidiaries in low tax countries often in tax havens. Because this practice is so difficult to detect, no one knows the full scale of the problem.” (It is likely equal to or greater than flows from Trade Misinvoicing.)

Africa is the largest victim, so much that it is “effectively a net creditor to the rest of the world.”

“After the wealthy countries have invested in their poorer neighbors, they may continue to own them indefinitely, and indeed their share of ownership may grow to massive proportions, so that the per capita national income of the wealthy countries remains permanently greater than that of the poorer countries, which must continue to pay to foreigners a substantial share of what their citizens produce (as African countries have done for decades).” — Thomas Piketty

“If we tally up all types of legal and illegal financial flows, including investment, remittances, debt forgiveness and natural resource exports, we see that Africa sends more money to the rest of the world than it receives.”

Developing countries are being deprived of trillions per year even if we ignore trade misinvoicing with regard to services. (25% of global trade.)

This situation has not been around forever. These countries used to have the ability to hold up suspicious transactions. The WTO argued that this made trade too inefficient.

“Since at least 1994, customs officials have been required to accept invoiced prices at face value, barring exceptional circumstances. As a result, corporations have free rein to write out their invoices however they please, with little risk of being called out.”

Secrecy jurisdictions (tax havens) protect tax evaders, arms smugglers, and terrorists alike. The total amount of wealth stored in these tax havens is incalculable. Low ball estimates range from $20 trillion to over $30 trillion.

“The problem with tax havens is not only that they facilitate the theft of capital. or that they prevent governments from capturing revenues. but also that they induce what analysts call ‘tax competition’ or ‘tax warfare’. Tax havens have set off a kind of global race to the bottom, with countries competing to offer low tax rates to foreign investors in order to attract them in. This constant pressure to reduce taxes makes it very difficult for parliaments and governments to make rational decisions about tax legislation, or to plan their budgets into the future.

Some economists nonetheless believe that the tax haven system is justifiable according to neoliberal theory: they claim that money should be allowed to move freely around the world in search of the best tax rates. But much about the tax haven system runs directly against the principles of free markets. For example, trade mispricing makes a mockery of the idea of ‘market prices’: the prices of many of the goods that get shipped around the world have nothing to with the market at all — they are simply invented out of thin air.”

“It is important that we expand our conception of corruption to include: illicit outflows, anonymous companies, secrecy jurisdictions, and so on in order to understand how the problem of corruption actually is. Inasmuch as these practices siphon resources out of the global South, they contribute significantly to global poverty and inequality, and yet the mainstream definition of corruption does not encompass them, and they are absent from the UN Convention. Instead, the corruption narrative diverts our attention away from these exogenous problems and places the burden of blame on developing countries themselves.”

Climate Change

The Global South which has contributed the least to global climate change will face the most severe consequences with the least ability to deal with them.

Consequences are very interconnected and mutually reinforcing. I evaluate the specific relationships here.

“CHINA” has become the mental refuge for people unable to deal with the implications of climate change on the present economic system. Now that China has passed the US in total carbon emissions it is sorely tempting to absolve ourselves of our historical and ongoing role in imminent climate crisis.

It’s important to keep in mind a few things. For one, significant US carbon emissions are effectively outsourced to and therefore blamed on China. (As well as plenty other countries.) Goods produced in China then shipped to America for American consumption are not considered American emissions.

Even without adjusting for this, the US still triples Chinese emissions on a per capita basis, which is the actually meaningful metric. (If we assume the proper metric is a per country basis, then the ideal solution would be to break up China into several smaller countries.)

Without earnest international action the modest reductions in poverty achieved in the global South will be more than reversed within decades.

“How are states to invest in building a zero-carbon infrastructure when they are subjected to austerity and privatisation?

How are governments supposed to tax and regulate fossil fuel companies when the very idea of taxation and regulation has been stigmatised as socialist or totalitarian, and even rendered illegal according to some international trade agreements?

How are we supposed to subsidise innovation in renewable energies when subsidies have been banned for running against the principles of ‘free trade’ (with suitable exceptions made for US agribusiness and fossil fuels of course.)”

Part 4 Closing the Divide

From Charity to Justice

Prevention is always better than cure… Pay attention to systems not just symptoms.

5 Ideas for a fairer global economy.

1. Debt Resistance

Abolish debt burdens of developing countries. Reinstall sovereign control of economic policy. Countries can look after their people and develop their economies instead of giving Tony Soprano his cut.

“This will be a difficult battle, of course, since creditors stand to lose a great deal. Some that are overexposed to debt in heavily indebted countries might even go bankrupt, But that is a small price to pay for the liberation of potentially hundreds of millions of people. If we abolish the debts, nobody dies — the world will carry on spinning. Debts don’t have to be repaid, and in fact they shouldn't be repaid when doing so means causing widespread human suffering.

Some NGOs have called for debt ‘relief’ or even ‘forgiveness’, but these words send exactly the wrong message. By implying that debtors have committed some kind of sin, and by casting creditors as saviours, they reinforce the power imbalance that lies at the heart of the problem. The debt-as-sin framing has been used to justify ‘forgiving’ debt while requiring harsh austerity measures that replicate the structural adjustment programmes that contributed to the debt crisis in the first place, effectively saying ‘we will forgive your sins, but you will have to pay the price’. In other words, until now, debt forgiveness has largely just perpetuated the problem. If we want to be serious about dealing with debt, we need to challenge not only the debt itself but also the moral framing that supports it.”

This applies particularly to “Dictator debts” as these were never agreed to by these populations in the first place, and likely never meaningfully benefited them. It also applies to debts which have been paid back in principle but remain outstanding due to compound interest.

“We might suggest that poor countries below a certain development threshold that have already paid their debts plus the equivalent of a modest rate of interest — say 2–3 percent per year at most, enough to cover the creditors’ inflation losses — deserve to have the rest of their debt burden written off. This would be the same thing as retroactively imposing interest rate caps on already existing loans, to make them more affordable.”

The World Bank will of course not be particularly eager to change, but there is an opportunity for alternative institutions like the New Development bank, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank which could offer low interest finance to developing countries sans SAP’s they could help free the Global South from their creditors. (Could is not the same as will.)

2. Democratize Global Institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and WTO.

The Global South holds most of the world’s people. If we believe in democracy they should have a proportionate say in global policies that significantly affect them.

“The presidents of the World Bank and the IMF should be decided not by fiat by the US and Europe, as is presently the case, but instead by merit-based candidacy and democratic election”

3. Fair Trade

“Trade could be conducted with an intentional bias towards poor countries for the sake of promoting development”

Free trade agreements should be negotiated publicly. Preferably all present agreements should be renegotiated under more transparent and democratic conditions.

Having full access to the draft proposals would allow vulnerable groups and advocacy organizations in rich and poor countries alike to push back against clauses that are harmful to people and the environment.

4. Just Wages

If companies can browse a global labor market searching for the cheapest workers, we need global labor standards as well, including a global minimum wage. Applying the same standard across the globe would be ham-fisted and problematic, but a solution could be to set the bar at 50% of the median wage in each country.

“Raising wages also has positive economic benefits: putting more money into the hands of ordinary workers stimulates demand and thus facilitates local economic growth, and it does so in a way that doesn’t depend on debt (unlike microfinance).

Of course, some might object that raising wages in poor countries might drive up the prices of their exports too much, leading to a drop in consumer demand and ultimately a rise in unemployment. But this fear is not well founded. There is no evidence that raising minimum wages has any negative effect on employment. Indeed, a recent study found that doubling the wages of sweatshop workers in Mexico would raise the price of clothes sold in the US by only 1.8 per cent -too little for most consumers in rich countries to notice. In fact, you could raise sweatshop wages by a factor of ten and consumers still wouldn’t be fazed: a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that people are willing to pay up to 15 per cent more on a $100 item and 28 per cent more on a $10 item — if it is made under ‘good working conditions’. There is a lot of room for wage growth before it begins to have any troublesome economic effects.

It might sound like a bureaucratic nightmare to manage, but the UN’s International Labor Organization has already claimed that it has the will and the capacity to govern a global minimum wage system.”

5. Reclaiming the Commons

Deal with the three mechanisms of plunder. Tax Evasion, Land Grabbing, Climate Change.

Change WTO invoicing standards. Allow customs to hold up suspicious transactions.

Close down the tax havens once and for all, require global financial transparency. Penalize bankers and accountants who enable tax evasion.

Require MNC’s to report profits where the economic activity actually takes place.

Impose a global minimum tax to put a floor on the race to the bottom.

Land grabs by corporations in the name of reducing hunger have dispossessed small farmers which risks increasing hunger.

Sidenote: In a world of climate change wreaking havoc in the global South I think there’s something to be said for sharing the likely uneven costs among larger groups of people. I’ll admit though, global South farm land reform is not exactly my forte.

“Implementing these interventions will require the political courage to stand up to the interests of the very powerful actors who extract so much material benefit from the present system, for they will not concede voluntarily. It will be a difficult battle, but not impossible.”

There are organizations fighting these fights such as the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America, the Asian Floor Wage Campaign, the tax Justice Network, and the Global Network of Small Farmers.

“As this book goes to press 690 institutions around the world - including universities, faith-based organizations, foundations, pension funds & governments - have divested their wealth from fossil fuels, pulling some $5.44 trillion out of the industry and redirecting much of this into renewables.”

If we were successful in removing the internationally enforced economic shackles on the global south, we face the problem of climate catastrophe on an even greater scale.

Increases in the material well being will inevitable bring increases in consumption and therefore resources. If we want sustainable global progress against poverty it will require a flattening of the distribution of resources. This is… untenable to say the least given the modern rhetoric of our economists and politicians.

GDP is a bad measure. It is known. Externalities are ignored, as are valuable activities which are not monetized.

“In the United States GDP has risen steadily over the past half century, yet median incomes have stagnated. The poverty rate has increased and inequality has grown. The same is true on a global scale: while global real GDP has nearly tripled since 1980, the number of people living in poverty, below $5 per day, has increased by more than 1.1 billion. Why is this? Because past a certain point, GDP growth begins to produce more negative outcomes than positive ones.”

There are no more frontiers where accumulation doesn’t harm someone else via enclosure, soil degradation, water pollution, climate change etc. Trying to convince our leaders that this is a problem is like speaking another language.

“What we measure informs what we do, and if we’re measuring the wrong thing, we’re going to do the wrong thing.” — Joseph Stiglitz

An ostensible indication of improvement is that domestic consumption in wealthy countries is decreasing, or at least not significantly increasing. The problem is this is only the case if we exclude the footprint involved in production and shipment of those goods which have been outsourced to the global South.

BECCS Bio Energy Carbon Capture and Storage: Develop tree plantations to absorb carbon, cut them down, ship the pellets around the world, and burn them to create energy while capturing the carbon produced and storing it in the ground. The only problem is that the technology does not exist.

“Plus, even if we somehow managed to get BECCS online tomorrow, we don’t have enough land on the planet to make it work. We would need to create a plantation three times the size of India to harvest year after year, decade after decade, and without taking away from the agricultural land that we need to feed the world’s population.”

Besides fossil fuels we have to deal with deforestation which releases carbon and reduces carbon storage. Livestock farming produces methane and nitrous oxide. “Livestock farming alone contributes more to global warming than all the cars, trains, planes, and ships in the world.”

Regenerative Farming: A rare source of climate optimism in that it effectively sequesters carbon while increasing long term yields due to higher fertility, and resilience to drought and flooding.

Renewables help, but there’s no getting around the fact that rich countries need to downscale production and consumption significantly, and poor countries will have to follow suit after a few years.